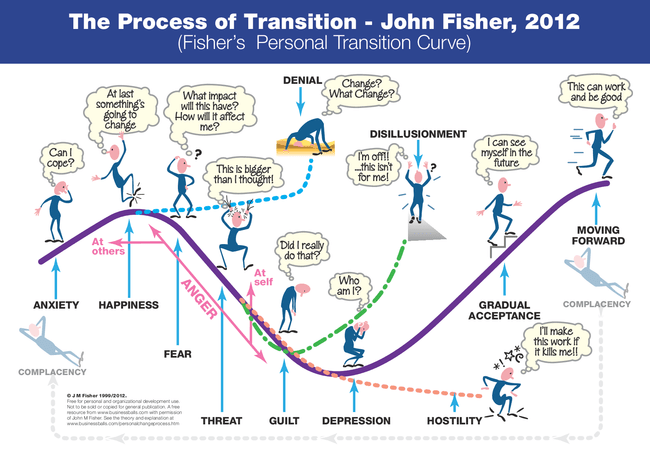

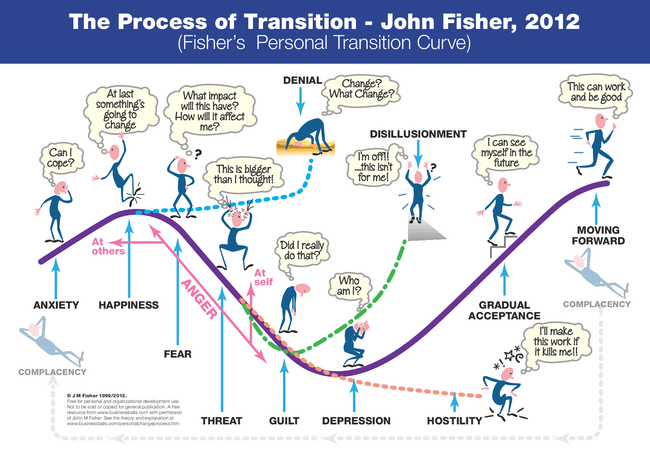

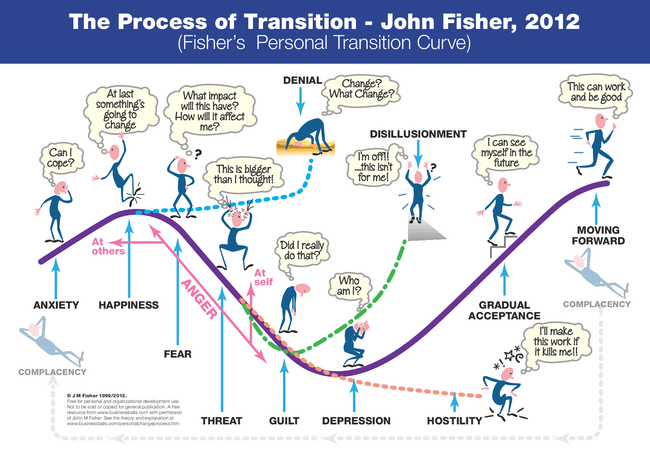

John Fisher (Leicester University) is a well-respected business psychologist whose work on constructivist theory in relation to service provision organisations produced a model in 1999 of personal change, The Personal Transition Curve, which provides us with an analysis of how individuals deal with personal change. This was updated in 2012 and represents a development of The Change Curve, widely attributed to psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross and her work on the process of bereavement and grief.

Business theory may seem a long way away from gender studies but it is relevant to us when we have to manage the effect that our transition has on those around us in order to retain our personal relationships intact during our transition. Understanding Fisher’s model and the phases that individuals go through when faced with change (of any sort) can help prepare us for the reactions of those closest to us around our transition. Take a look at Fisher’s 2012 model and there are probably some phases that seem familiar to you, reactions that you have witnessed in those around you to your news.

Let’s examine the stages and apply them to the process of gender transitioning:

Let’s examine the stages and apply them to the process of gender transitioning:

Anxiety

The awareness that events lie outside one’s range of understanding or control. Fisher believes the problem here is that individuals are unable to adequately picture the future. They do not have enough information to allow them to anticipate behaving in a different way within the new organisation. They are unsure how to adequately construe acting in the new work and social situations.

This is familiar to trans* people. The condition of gender dysphoria and the stages of treatment that trans* people have to go through is not well understood and outside most people’s experience. This breeds a fear of the unknown – what will life be like for the trans* person and what will life be like for those closest to the trans* person?

It is up to us to reassure those around us that we can see the future and it is going to be an improvement on the present. Using testimonies from trans* people who have gone before us, such as can be found on YouTube, can help those around us visualise our future.

Happiness

The awareness that one’s viewpoint is recognised and shared by others. The impact of this is twofold. At the basic level there is a feeling of relief that something is going to change and not continue as before. Whether the past is perceived positively or negatively, there is still a feeling of anticipation and even excitement at the possibility of improvement. On another level, there is the satisfaction of knowing that some of your thoughts about the old system were correct (generally, no matter how well we like the status quo, there is something that is unsatisfactory about it) and that something is going to be done about it.

Trans* individuals may recognise this phase as the moment when people say, “We always knew you weren’t like other children”, and then congratulate you on having the courage to recognise it in yourself.

Fisher says that the happiness phase is one of the more interesting phases and may be (almost) passed through without knowing. In this phase it is the “Thank goodness, something is happening at last” feeling coupled with the knowledge that, if we are lucky/involved/contribute, things can only get better.

Significantly for trans* individuals, if we can start interventions at this stage we can minimise the impact of the rest of the curve and virtually flatten the curve. By involving, informing, getting a “buy in” at this time we can help people move through the process. This is where availability of factual information can help maintain the “happy” feeling. Collect a number of different sources for your family to read that underline the positives of transitioning so they can choose the medium that suits them: health leaflets, transgender biographies, sympathetic documentaries and Internet resources. Encourage your friends and family to talk to you about your transition and accept any help that they may offer in order to involve them in your transition.

Fear

The awareness of an imminent incidental change in one’s core behavioural system. People will need to act in a different manner and this will have an impact on both their self-perception and on how others externally see them. However, in the main, they see little change in their normal interactions and believe they will be operating in much the same way, merely choosing a more appropriate, but new, action.

According to Frances (1999), fear and threat are the two key emotions that will cause us to resist change.

Threat

The awareness of an imminent comprehensive change in one’s core behavioural structures. Here people perceive a major change to what they believe to be their core identity or sense of self. The realisation that the change will have a fundamental impact on who we are, how we see ourselves and what is key in our personality to us as individuals. This is the shock of suddenly discovering you’re not who you thought you were! It is a radical alteration to our future choices and other people’s perception of us as individuals. Our old choices are no longer ones that will work. In many ways this is a “road to Damascus” type of life-changing experience. In this phase, people are unsure as to how they will be able to act/react in what is, potentially, a totally new and alien environment; one where the old rules no longer apply and there are no new ones established as yet.

It is key for trans* people to combat these two phases by being clear and concise about what is going to happen to them physically, what the timescale is for their transition, when others can expect to see physical changes, when others need to start using correct names and pronouns, etc. Being clear about what you need from those around you creates the new set of rules that friends and family can use to replace the old rules that no longer apply, giving them some stability.

Guilt

An awareness of a dislodgement of our self from our core self perception. We are not who we thought we were! Once the individual begins exploring their self-perception, how they acted/reacted in the past and looking at alternative interpretations they begin to re-define their sense of self. This, generally, involves identifying what are their core beliefs and how closely they have been to meeting them. Recognition of the inappropriateness of their previous actions and the implications for them as people can cause guilt as they realise the impact of their behaviour. Another of the emotions that may have an impact here is that of shame. This is the awareness of a negative change in someone else’s opinion of you from what you think it should be. The recognition of this shift in our own and other people’s opinion then leads into the next stage.

This is a particularly resonant phase for partners and parents who may have insisted, at various times in the trans* person’s life, that they dress or look a certain way. Depending on how forcefully this was done, those around the trans* person may feel guilty about this. It is up to us as trans* people to make it clear to those who love us that we understand they could not have known what they were doing and acknowledge that they meant well by their actions at that time.

Shame is one of the most destructive emotions for trans* people, when our family and friends feel ashamed of us because they receive, or think they will receive, negative opinions about us from others. Being out and proud of ourselves can help those closest to us to see that the world, by and large, is accepting of trans* people. Recounting your positive experiences of telling people can also help persuade friends and family that there is nothing to be ashamed of.

Depression

The awareness that our past actions, behaviours and beliefs are incompatible with our core construct of our identity. The belief that our past actions mean we’re not a very nice person after all! This phase is characterised by a general lack of motivation and confusion. Individuals are uncertain as to what the future holds and how they can fit into the future “world”. Their representations are inappropriate and the resultant undermining of their core sense of self leaves them adrift with no sense of identity and no clear vision of how to operate.

For trans* people this often manifests itself with declarations from friends and family that we are no longer who they thought we were or that everything they thought they knew about us was a lie. This, of course, is untrue. We need to remind them of all the things that have not changed about us. Gender is only one aspect of a person, it is not the whole. Undertaking activities with your friends and family that you have always done together can be a way to remind them that you haven’t changed and there are still lots of things about your relationship that are familiar.

Gradual acceptance

Here we begin to make sense of our environment and of our place within the change. In effect, we are beginning to get some validation of our thoughts and actions and can see that where we are going is right. We are at the start of managing our control over the change, making sense of the “what” and “why” and seeing some successes in how we interact – there is a light at the end of the tunnel! This links in with an increasing level of self-confidence and an awareness of the goodness of fit of the self in one’s core role structure, i.e. we feel good that we are doing the right things in the right way.

Moving forward

In this stage, we are starting to exert more control, make more things happen in a positive sense and are getting our sense of self back. We know who we are again and are starting to feel comfortable that we are acting in line with our convictions, beliefs, etc and making the right choices. In this phase we are, again, experimenting within our environment more actively and effectively.

Complacency

It has also been suggested that there is also actually a final (and/or initial stage) of complacency (King 2007). Here people have survived the change, rationalised the events, incorporated them into their new construct system and got used to the new reality. This is where we feel that we have, once again, moved into our comfort zone and that we will not encounter any event that is either outside our construct system (or world view) or that we can’t incorporate into it with ease. We know the right decisions and can predict future events with a high degree of certainty. These people are subsequently laid back, not really interested in what’s going on around them and coasting through the job almost oblivious to what is actually happening around them. They are, again, operating well within their comfort zone and, in some respects, can’t see what all the fuss has been about. Even though the process may have been quite traumatic for them at the time!

Annoying though this may be, especially if you have had to invest time in supporting them through the transition curve, don’t allow yourself to get angry at their denial of the effort it has taken to reach this level of acceptance of your transition. Just be grateful that they are there!

Now, let’s look at some of the ways that the transition curve can get derailed into negative emotions that go nowhere:

Denial

This stage is defined by a lack of acceptance of any change and denies that there will be any impact on the individual. People keep acting as if the change has not happened, using old practices and processes and ignoring evidence or information contrary to their belief systems. In many ways when we are faced with a problem, or situation, we don’t want, or one that we believe is too challenging to our sense of self we constrict or narrow our range of construction. In this way we eliminate the problem from our awareness. The “head in the sand” syndrome: if I can’t see it, or acknowledge it then it doesn’t exist!

This one is horribly familiar to lots of trans* people. The constant use of old pronouns and old names is a classic example of where a person is in denial about your transition. Be patient with this one. Listen to them and attempt to understand where they are at that moment. Timing is important when managing change so don’t try to move them onto the next stage before they are ready for it. You will be ahead on them on the transition curve so you will know when the time is right to move the discussion on.

Anger

Fisher came to recognise over time that there seemed to be some anger associated with moving through the transition curve, especially in the earlier stages as people start to recognise the wider implications of change. This is not always present as it seems to be dependent on the amount of control people feel they have over the overall process. The focus of the anger also changes over time. In the first instance, for those where change is forced on them, the anger appears to be directed outward at other people. They are blamed for the situation and for causing stress to the individual. However, as time progresses and the implications grow greater for the individual, the anger moves inwards and there is a danger that this drives us into the guilt and depression stages. We become angry at ourselves for not knowing better and/or allowing the situation to escalate outside our control.

A lot of trans* people experience the anger of their friends and family at the changes being forced on them by the transition. Unfortunately, this anger frequently is directed at the trans* person rather than at the situation that those closest to us find themselves in. This is unfair but, if we understand why it is happening, we can recognise it for what it is and work through it. Hurtful and insulting remarks may be said in the heat of anger. We must try not to get angry ourselves and reply in kind but, instead, realise that they are not meant personally. They are a natural reaction to a situation that is out of an individual’s control.

Disillusionment

The awareness that your values, beliefs and goals are incompatible with those of the organisation. The pitfalls associated with this phase are that the employee becomes unmotivated, unfocused and increasingly dissatisfied and gradually withdraws their labour, either mentally (by just “going through the motions”, doing the bare minimum, actively undermining the change by criticising/complaining) or physically by resigning.

The undermining, criticising, and withdrawal of support may be familiar to trans* people. Often this happens to a friend or family member who has previously seemed supportive of our transition. One way to re-engage them with your transition is to ask their opinion about an aspect of transitioning in order to involve them in the process again. It could be something as minor as asking them to go shopping with you for some new clothes and taking their advice on what might suit you, or it could be a more significant involvement such as asking them to help plan your travel and accommodation for a hospital trip.

Hostility

The continued effort to validate social predictions that have already proved to be a failure. The problem here is that individuals continue to operate processes that have repeatedly failed to achieve a successful outcome and are no longer part of the new process or are surplus to the new way of working. The new processes are ignored at best and actively undermined at worst.

It is possible that some people in your life are not able to move forward and get stuck in the stages of denial, disillusionment or hostility. You may not be able to help everyone move through the change process, despite your best efforts. If this happens, your time might be better spent working with those who are moving through the curve and see your transition as a positive thing. These people can act as “champions” and may,in the long run, support those stuck in denial, disillusionment or hostility to reach the same view.

Summary

It can be seen from the transition curve that it is important for an individual to understand the impact that the change will have on their own personal construct systems, and for them to be able to work through the implications for their self-perception. Any change, no matter how small, has the potential to impact on an individual and may generate conflict between existing values and beliefs and anticipated altered ones.

To help people move through the transition effectively we need to understand their perception of the past, present and future. What is their past experience of change and how has it impacted on them, how did they cope, what will they be losing as part of the change and what will they be gaining? Our goal is to help make the transition as effective and painless as possible. By providing education, information, and support we can help people transition through the curve and emerge on the other side. Trans* Jersey has posted a page of change management tools that may help you manage your transition and the acceptance of those around you. Also, you may want to read around the subject of mechanisms for coping with change. There’s a good primer here from Mind Tools.

Each person will experience transition through the curve at slightly different speeds. Much of the speed of transition will depend on the individual’s self-perception, locus of control, and other past experiences, and how these all combine to create their anticipation of future events. The more positively you see the outcome, the more control you have (or believe you have) over both the process and the final result, the less difficult and negative a journey you have.

You can find out more about John Fisher’s process of personal transition here where the model’s history is discussed.